Last Monday, while monitoring and mixing this podcast at midday, a massive blackout plunged this beach town and the entire peninsula into a real-life episode of an apocalyptic future. I was fortunate to be seated at my desk, unlike the poor bastards trapped inside lifters or commuting on trains and subways, standing and packed one against the other like a can of sardines. The only lifeline was the juice of my iPhone, which kept me connected abroad until the network coverage collapsed as well.

As soon as I heard it wasn't a local blackout but by all odds affected Spain and Portugal, I went up to the rooftop terrace to check if the planes’ trails were drawn in the sky, and everything was quite normal for an April day. The tireless sexual revelry of birds mating, the hubbub of swifts flying around me, and the mist of yellow pollen from the mix of pine and oak wood, floating in the valleys of the nearby hills. Why should I be worried?

So, expecting to stay without power for at least 24 hours, given that we are ruled by simpletons crowing about our renewable energy production, I set a leftover of stewed beans and peas to warm up under the glorious sun, well covered to avoid the curious wasps and bees and the looming sea gulls, and returned to my desk to sharpen the pencils, gather paper, and get ready to take casual notes to enjoy a wonderful reading.

From the book stack, I randomly chose a British author I had adored when he was young, and his literary tricks were a novelty for me. I’m talking about Julian Barnes and one of his latest works, The Sense of an Ending. But since the old friend Julian became a solemn widower of Pat Kavanagh, his writing has become simply sad. It evokes the same bottomless loss and grief I found reading Joan Didion’s The Year of the Magical Thinking.

About Julian Barnes, I still recall reading The History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters the first year of the 90s. It was a jaw-dropper, and the unnumbered half-chapter titled Parenthesis was so good to learn the lines by heart. I did many casual renditions; my best one was whispering away in a bookstore to a ballsy sweetheart once I had. So, my actual disappointment is that, after being a loyal reader and reciter of his works for decades, the bond with this author is not there anymore. Surely it's just me, who doesn't find amusing the double sex lives and nor the love triangles as I did in my 20s. I guess everything has its own time.

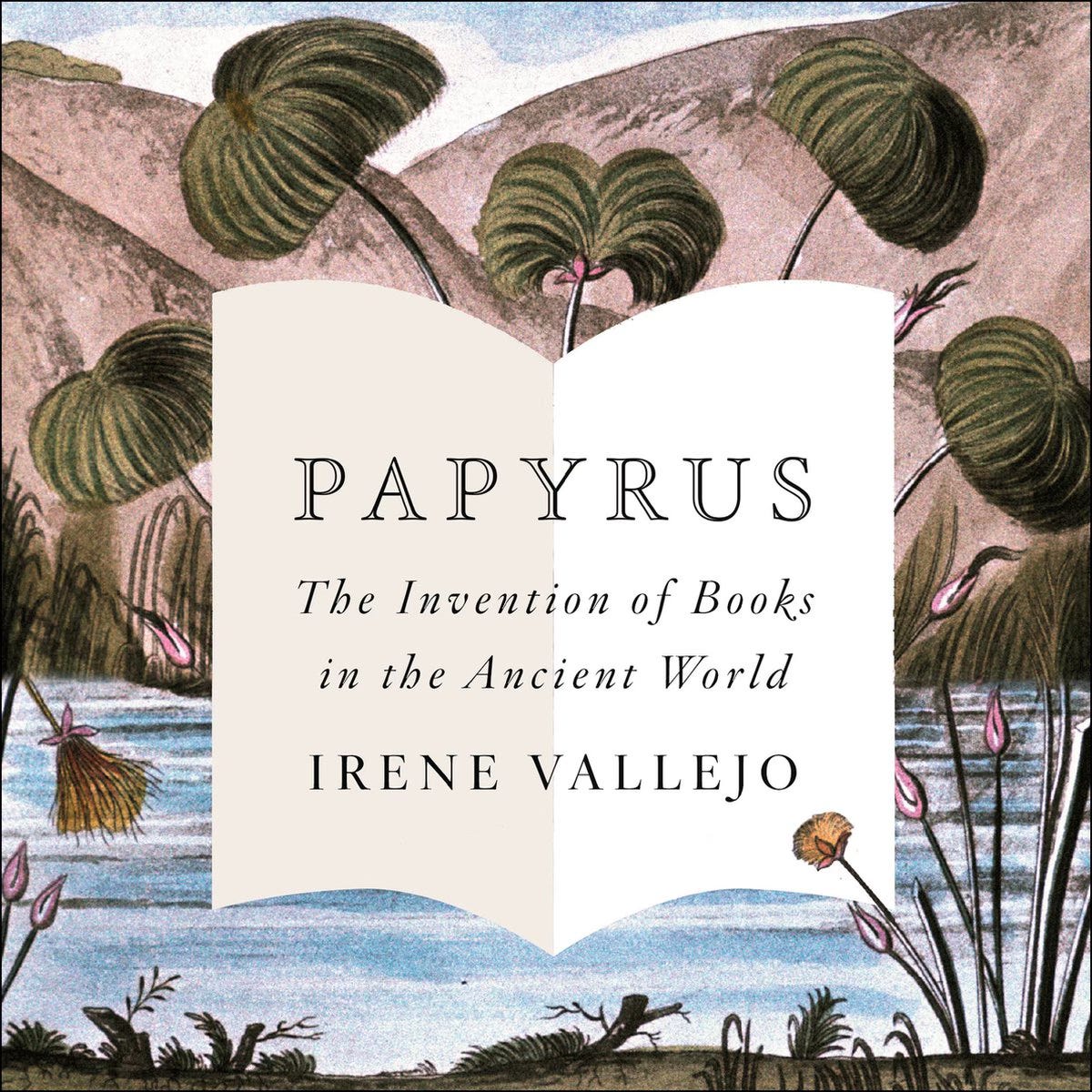

What really set me in reading mode was a wonderful essay from the Spanish scholar Irene Vallejo, originally titled El Infinito en un junco–the boundless in a reed–but the translator Charlotte Whittle tossed William Blake's Auguries of Innocence obvious analogy to simply leave it as Papyrus.

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.

What have you done, Charlotte? You are supposed to translate the concept and not the idea! Which differs in its identity, similarity, opposition, and analogy. The Italian expression 'traduttore, traditore'–translator, traitor–refers to the implicit imprecision of the act of translating.

Anyhow, this is a book about libraries of the past and of the present, and also about the booksellers. As Irene will tell the reader, you can create a parallel world when opening a book and reading every word, and yet at any moment you can move your gaze away and return to the world that is. When you think of the first letters on clay to papyrus and move through the ages to leather-bound books to the modern-day books on both paper and then those words read on electronic devices, think back to where it all began in the ancient world.

My own Irene Vallejo’s blackout party, and the following is not random, began with her description of the lost world of storytelling, in the small palace of a local lord in a time before writing was widespread, when language was fleeting, made up of air and echoes. The Greek Homer called it "winged words" from the point of view of his blindness. Which isn't yet literature, since it isn't set down in letters or writing.

Bards were not only wandering musicians but also skilled memory men, with a repertoire that captivated their masculine audiences for long hours with all kinds of epic. And had no sense of authorship at all, like a jazz musician who takes a popular tune and embarks on a passionate improvisation without a score. Or what we know as variations on the same theme. Individual expression belongs to the time of writing and the prestige of artistic originality had yet to flourish.

The night fell, and the power still wasn't back. And for a stargazer, it was beautiful to look up to the vault of heaven with zero light pollution. It was the night of the times. Then, on the other side of Main Street, power came back, and normality was restored. But the other half of the beach town remained in absolute darkness for one hour more. And I was already missing darkness when I finally turned on the light.

As anyone who has experienced a blackout can attest, when the power returns, even at midnight, it's a boost for morale. And I have a confession to make. I couldn't wait to know if Apple had saved my work! One has these stupid fears, perfectly normal after some bad experiences with disappeared files. So, I put on the open back studio headphones for critical listening, to resume my slow learning as a sound engineer with the digital audio workstation–always feeling a mix of infinite joy and a pang of shame for my lack of knowledge each time I learn something new–cranking up the volume to hear all my blunders and correct them, and also promising to outdo myself with each new release.

Share this post