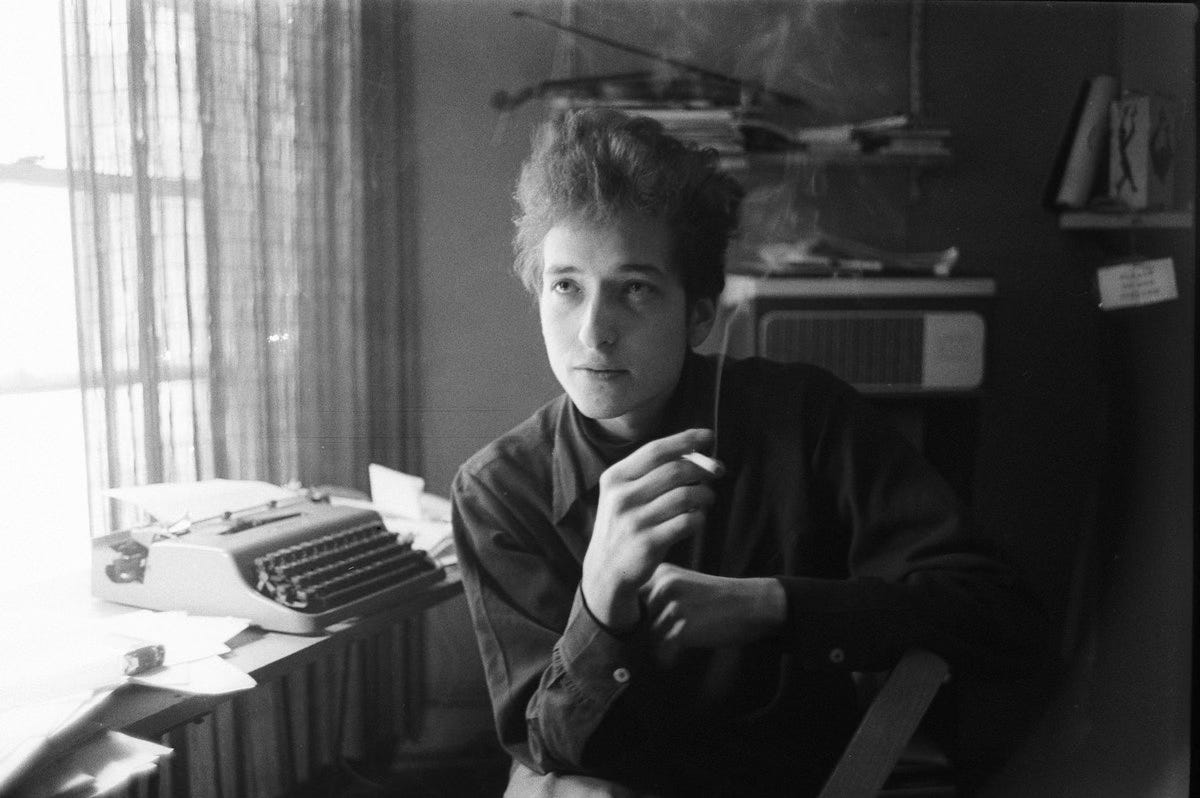

I have mixed feelings after watching Chalamet’s Bob Dylan impersonation in the film A Complete Unknown. It is a superb acting performance. Still, there is an unsurmountable distance between an actor cast solely based on his looks and chameleonic aptitudes, and the real deal that shrines through, which is often disconcerting. The first impression of a successful folk star like Joan Baez was "I was bowled over. I never thought anything so powerful could come out of that little toad."

The biopic tries to portray Robert Allen Zimmerman, a Jewish lad from Minnesota that conquered as Bob Dylan in the early 60s the New York folk scene as a wonderkid. Nobody made it so fast, not even Joan Baez. These two became the protest song duo, performing With God On Our Side in the Newport Folk Festival 1963. That was the summer before President Kennedy was murdered.

Since then, the musician began a singular career. Something between a reluctant prophet that speaks in riddles and an electrifying I-don't-give-a-damn Like a Rolling Stone, roaming around the world on an endless tour, and clearly profitable, still performing at 80 years old with a gravelly whisper for a voice that has made of his once nasal tone a relic from a distant past.

Credit where credit is due. If someone truly deserved a Literature Nobel Prize, it was Bob Dylan. His lyrics certainly were not brainy novels, but rich songs riveted with mighty poetry and strong melodies that stuck deep in the collective imagination of three generations, me included. Fret not, I'm not going to make a list, but surely I'm going to resort to more hyperlinks.

In the Nobel lecture he recorded, I was moved by such common sense, anticipating the backslash of the writers’ guild, who were outraged that a performer, rather than an author, was being awarded. Dylan pointed out that "the words in Shakespeare's plays were meant to be sung, not read on a page."

He was damn right. All those lyrics from a love songs we have listened sometimes had a musical origin that began with wandering poets and performers called troubadours, a word that comes from the Early Middle Ages, during the Islamic expansion that reached the Iberian Peninsula, and it is Arab for "taraba", entertain or just sing for your supper. The roots of those performers are intertwined with the Arab-Andalusian music, brimming with Persian musical instruments like the lute, oud, daf, rebec, and the hypnotic percussion from Isfahan played with on drums like the tombak.

The Arabs valued Persia craftsmen and, above all, Persian music and singers. The Umayyads, both in Damascus and later in Al-Andalus, imported performers from Baghdad in the 8th century by the hand of the emir Abd al-Rahman like Abu al-Hasan, better known for his nickname Ziryab, Persian and Kurdish word for blackbird.

This musical poetry wasn't performed in the streets but in luxurious walled gardens called paradise, from the old Persian "pairi dez", with a profusion of sweet orange trees, water fountains, and exotic Eastern botany species, such as irises, jasmine, narcissus and marigolds. The gardens of al-Hambra in Granada have since then still remained like an untouched marvel.

Those first love songs dealt with melodramas like the old man’s jealousy for his enigmatic young bride, who yearned to escape with her mad lover. Before their wedding, he fled into the wilderness, where he would recite poetry to himself or write in the sand with a stick, becoming detached from the physical world. This left her heartbroken, confined to a golden cage, until she eventually lost hope and gave up on life. News of her death reached the mad lover in the wilderness. He travelled to the place where she had been buried, and there he wept, succumbing to the impossible grief and dying at the graveside of his one true love.

Audience reveled in "sama" or what we know as a trance or ecstasy, because a song about undying love involved devotion and the annihilation of the self. That love also means the longing for spiritual union with the divine. Remember Eric Clapton playing Layla to see that nothing has changed along the centuries in the story of the mad lover Majnun.

These wandering poets traveled to Christian courts in Southern France. And from the early contacts between these Eastern performers with the eclectic fusion of Arabic and Spanish and Jewish in the Mozarabic culture, coupled with the Occitan new version of Christianism known as Catharism–which main tenets were the recognition of the divine female principle as the goddess Sophia–lead to the popularity of "fin'amor" or courtly love, under the patronage of William IX, Duke of Aquitaine.

It beats me how this mirage of the Early Middle Ages would morph into the millennium along the Carolingian feudalism system with a treasure trove of chanson de geste as The Song of Roland, Cantar de mio Cid, and The Song of Nibelungs. This was the backbone of the new knighthood creed, the steroids for warmongering kings and popes that unleashed eight Crusades to conquer Jerusalem, and also to raze the hip and loving Occitania massacre of Cathars included during the Albigensian Crusade.

Back to Bob Dylan, when it was announced in 2016 that he would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature he remained in silence for weeks to excuse his presence for previous commitments. Until he knew that at least he had to deliver a lecture to cash the 8 million Swedish kroner, almost a million dollars. So, he wrote the Nobel lecture about having an epiphany when he was eighteen, going to a Buddy Holly concert in Duluth, Minnesota, just before he died in a plane crash two days later—the Day the Music Died. And a Dylanesque dissertation about three books that leaked into his lyrics: Moby Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front, and of course The Odyssey, to clinch the matter with a deep reflection on the warrior Achilles in the Underworld, where Odysseus found him sad and completely out of place.

Nostalgia was for Achilles the venom of being the king of the Underworld, so that the hero "would rather be a serf under a poor man's roof that has scarce bread for his household, if only I might be alive upon the earth."

With his playful touch, Bob Dylan concluded:

"That’s what songs are too. Our songs are alive in the land of the living. But songs are unlike literature. They’re meant to be sung, not read. The words in Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be acted on the stage. Just as lyrics in songs are meant to be sung, not read on a page. And I hope some of you get the chance to listen to these lyrics the way they were intended to be heard: in concert or on record or however people are listening to songs these days. I return once again to Homer, who says, “Sing in me, oh Muse, and through me tell the story.”

Share this post